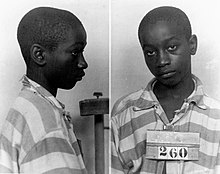

George Stinney was the youngest American to be executed in the past century, at 14 years old; before he was Inmate No. 260, his baleful countenance captured in a monochrome mugshot; before he was hauled away by white men in black cars, George Stinney was the beloved older brother of Amie Ruffner.

George and Amie lived with their siblings and parents in a three-room house owned by the lumber company that dominated Alcolu, South Carolina. Alcolu was like countless segregated communities across the Jim Crow South, a place where white and black laborers worked side by side in the saw mill but retreated to separate neighborhoods and churches at day’s end, separated by a set of railroad tracks.

On March 25, 1944, the bodies of two white girls who’d gone missing the day before were found in a watery ditch on the property of George Burke Sr., a prominent manager at the saw mill where most of the men in Alcolu earned their living. It was Burke’s search party that discovered the corpses, bludgeoned to death and pinned beneath a bicycle the girls were seen riding. George and Amie were among the last people to see the girls alive.

That afternoon, George Stinney was led from his home in handcuffs as Amie cowered in the family’s chicken coop, terrified. “George,” she screamed after him, “are you leaving me?” They were the last words she would say to her brother. As news spread of his arrest, George’s father was fired from his job at the saw mill. His family was forced to flee town ahead of a lynch mob.

George Burke Sr. served as foreman of the coroner’s inquest jury and was a member of the special grand jury convened to hear Stinney’s case despite also being a named witness. Stinney’s family was too afraid to attend the trial, so George faced his accusers alone. The local authorities pointed to Stinney’s confession,

"It may be interesting for you to know that Stinney killed the smaller girl to rape the larger one. Then he killed the larger girl and raped her dead body. Twenty minutes later he returned and attempted to rape her again, but her body was too cold. All of this he admitted himself."

likely coerced; Amie, who could have provided her brother with an alibi, was not called to testify. At the end of a three-hour trial, a jury of white men took just 10 minutes to find Stinney guilty. He was sentenced to the electric chair. His court-appointed lawyer didn’t bother with an appeal.

"It may be interesting for you to know that Stinney killed the smaller girl to rape the larger one. Then he killed the larger girl and raped her dead body. Twenty minutes later he returned and attempted to rape her again, but her body was too cold. All of this he admitted himself."

likely coerced; Amie, who could have provided her brother with an alibi, was not called to testify. At the end of a three-hour trial, a jury of white men took just 10 minutes to find Stinney guilty. He was sentenced to the electric chair. His court-appointed lawyer didn’t bother with an appeal.

On June 16, 1944, George Stinney, standing 5-foot-1 and weighing a scant 95 pounds, was strapped into a chair designed for adults. Contemporary news clippings claim the executioners sat him on books so he would reach the headpiece. Until the end, Stinney was bewildered. “Why,” he asked his cellmate, “would they kill me for something I didn't do?”

Stinney's trial had an all-white jury, as was typical at the time. As most blacks were still disenfranchised and prohibited from voting, they could not be selected as jurors. More than 1,000 whites crowded the courtroom, but no blacks were allowed.

Other than the testimony of the three police officers, at trial prosecutors called three witnesses: Reverend Francis Batson, who discovered the bodies of the two girls, and the two doctors who performed the post-mortem examination. Conflicting confessions were reported to have been offered by the prosecution. The court allowed discussion of the "possibility" of rape although the medical examiner's report had no evidence to support this. Stinney's counsel did not call any witnesses, did not cross-examine witnesses, and offered little or no defense. The trial presentation lasted two and a half hours.

The jury took less than ten minutes to deliberate, after which they returned with a guilty verdict. Judge Ph sentenced Stinney to death by electrocution. There is no transcript of the trial. No appeal was filed by his defense attorney.

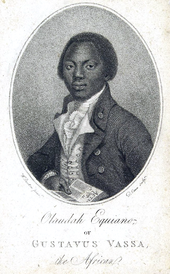

To weigh the weight of history directly and calls for a reckoning with the ongoing ways in which “the descendants of slaves are still very much enslaved.” 240 years before George Stinney was executed, many Southern settlements, “enslaved and freed Blacks outnumbered Whites. Threats to the institution of slavery (i.e., revolts, escapes) and maintaining the supremacy of Whites over Blacks were significant regional concerns.” Carolina, established on land occupied by indigenous peoples, was also a frontier space. Law enforcement was of paramount concern for white settlers, who sought “to regulate spaces that they did not own or fully control.”

Then and now, bondage was business, incentivized by economic concerns and a desire for profit. Today connecting our history of racialized social control and oppression to the present, noting that “when you look at the leading incarcerators on the planet today, they’re in the South.” The old masters sought wealth through plantation agriculture and trade in human chattel; today, mass incarceration is a $182 billion industry built on the backs of poor black and brown communities.

Then and now, questions of criminal justice and public safety were inextricably bound up in ideas of who deserved citizenship and inclusion, and whose bodies would lie outside the protection and status bestowed by the law. Black people have “existed either at the margins of citizenship…or have been excluded entirely,” .

In “My Dungeon Shook,” James Baldwin’s famous 1963 letter to his nephew and namesake, Baldwin wrote that white people are “still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.” Indeed, all Americans persist in darkness about our shared history, a painful record casting shadows and preventing us from seeing ourselves clearly today. But, piece by piece, the truth comes to light, its acknowledgement offering another opportunity to imagine our country anew—to make its promise whole.

Rather than approving a new trial, on December 17, 2014, circuit court Judge Carmen Mullen vacated Stinney's conviction. She ruled that he had not received a fair trial, as he was not effectively defended and his Sixth Amendment right had been violated. The ruling was a rare use of the legal remedy of coram nobis. Judge Mullen ruled that his confession was likely coerced and thus inadmissible. She also found that the execution of a 14-year-old constituted "cruel and unusual punishment", and that his attorney "failed to call exculpating witnesses or to preserve his right of appeal." Mullen confined her judgment to the process of the prosecution, noting that Stinney "may well have committed this crime." With reference to the legal process, Mullen wrote, "No one can justify a 14-year-old child charged, tried, convicted and executed in some 80 days," concluding that "In essence, not much was done for this child when his life lay in the balance."

Today in Alcolu, thanks to the efforts of local residents, a memorial gravestone to honor George Stinney sits alongside Sumter Highway. Its inscription reads: “George Stinney, Jr. October 21, 1929 – June 16, 1944. Wrongfully convicted, illegally executed by South Carolina. Conviction vacated by court order dated December 16, 2014.” It stands as a commemoration of a recent and wrenching past; as a prescient warning for our troubled present; as an accounting of our collective debt, to ensure that future generations of black boys will not be asked to pay with their lives.

The story of George Stinney is an everyday reminder that as long as black people all over the world wears those colours; black or brown, they remain a threat to the whites. The first thing they should see when they look at an African or a black person shouldn't be his colour rather it should be the part that makes them humans. Racial diversity will continue to influence the world regardless of how much we fight for equality but we must learn to be human beings first before becoming any other thing.

Hope you enjoyed this article? Kindly Drop Your Comments below.

Hope you enjoyed this article? Kindly Drop Your Comments below.